HOW TO BE A GOOD MINORITY?

Before the emergence of the modern republic, there was no such thing as being a minority. The republics of the ancient world were mostly homogenous small city-states and therefore had no minorities. To the extent that minorities did exist, such as the metics in Athens, they were not considered citizens.

By and large, the monarchies and empires of the pre-modern world had also avoided the question of how to be a good minority. Since nobody was a citizen and everybody was a subject, communities of dissenting beliefs (such as Jews in medieval Europe) simply existed at the pleasure of the ruler. Being “good” meant not causing trouble and being loyal to the king.

The advent of the modern state, however, has changed the meaning of being a minority. Mostly because it changed the relationship between the individual and the state. We are now citizens.

The Good Citizen

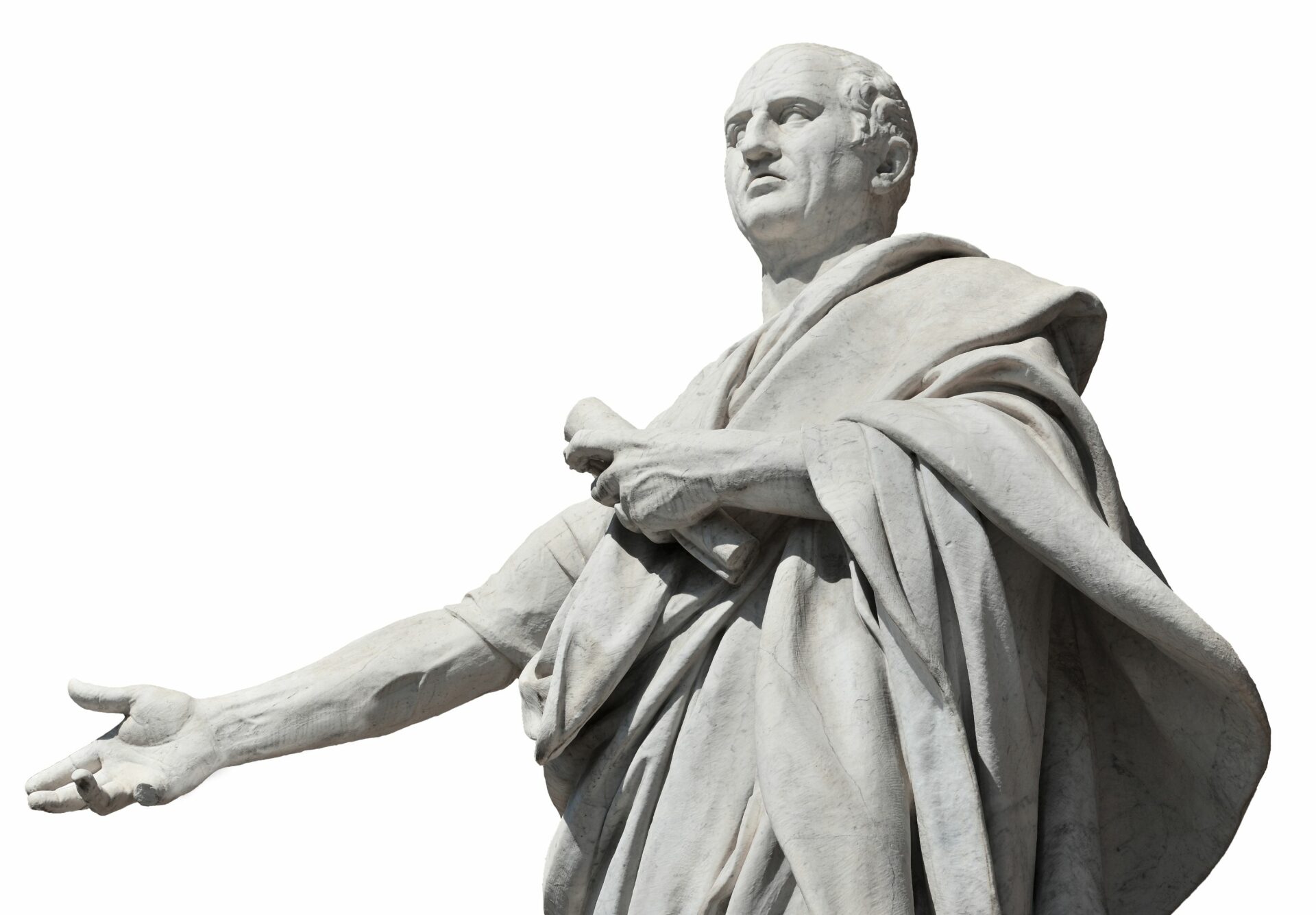

What does it mean then to be a good citizen? Drawing upon Aristotle and Cicero, and upon our American Founding Fathers, a good citizen is a custodian of the common good. A republic (res publica in Latin, meaning public things or a commonwealth) represents our common interest. It is a super-structure we’ve inherited by our forefathers, meant to improve our own affairs and to leave a good legacy to our posterity.

This is eloquently stated in the preamble to our Constitution. Our republic was devised “in order to form a more perfect Union… and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” A good citizen, then, like a good gardener is a good custodian. He tills the common garden and works to conserve and improve the common good.

When a good citizen votes, he votes seriously and serenely, adjudicating carefully the options with an eye towards the national interest. Indeed, this is what we call civic virtue.

Clearly, even the most virtuous citizen also thinks locally. And so, very cleverly, our political system builds from the bottom up, from counties and neighborhoods up to the federal republic. When voting locally (such as for a neighborhood alderman) we probably don’t think about the general interests of America. But we would probably avoid voting in any way that might risk America (say, for an alderman who wishes to dump our sewage into the water sources of another state).

Meaning, we each have to maintain a balance between the local and the national, the private and the common.

And that leads me to the question of what it means to be a good minority.

Being a Good Minority

Naturally, in a large republic, there may assemble communities of all sorts. This is simply the nature of the kind of countries and extended republics that we have. Certain communities share many things in common and thus form a majority (such as European Christians in America); others are more esoteric and may be rendered minorities (such as American Jews or Hindus or Muslims).

The majority should be reasonable towards minority communities: Assuming we are all to live together happily in one state, we cannot expect minorities to undo themselves. Jews will not convert to Christianity, Catholics will not become Protestants, and homosexual men will not begin pursuing women. The majority should also accept that members of a minority community may also share an increased affinity towards one another: Gays may feel a natural connection with other gays, Arabs may immediately connect with other lovers of hummus.

But minorities should also be reasonable. A homosexual should not expect the majority to change their ways for his own sake. He should not attempt to redefine the ways of the majority by demanding to see his own kind on TV through diversity quotas or to redefine the ancient traditions of the republic through the reinterpretation of marriage and child-rearing.

Just like a person voting locally, the minority should expect no more and no less than a carve-out, the ability to live their lives as they see fit within their own homes and their own communities.

In addition, like every citizen, a member of a minority group should be a good citizen. Recall, that means being a custodian of the common good. And so the phenomenon of “full-time” gays or “full-time” Jews who care about nothing else but their own sectorial needs, is not aligned with the idea of civic virtue.

A completely disengaged minority, happy in their protected carve-out, is also possible. Such a minority takes itself completely out of the life of the public life of the state. The Amish are the quintessential example for this and demonstrate both the limitations and the rather benign nature of such a lifestyle.

Clearly, if everybody were like the Amish, caring for nothing outside of their own micro-community, we would have no republic. But since the Amish keep to themselves, are limited in numbers, and place no demands upon the majority, they are completely benign. They can even be evaluated in utilitarian terms: They are great farmers and excellent custodians of rural America.

Let us review more cases.

All about the Jews

Ultra-Orthodox Jews. I believe this case is very similar to the Amish. The Ultra-Orthodox are an extremely ethnocentric community and one of America’s last traditional societies. By and large, they keep to themselves and place no demands on anybody beyond being left alone to manage their own affairs and institutions. Are they the ideal citizen who will take up arms in defense of the homeland? Definitely not. If everybody were like them, we would have no republic. But as they keep to their own carve-outs and enclaves, making no demands upon the common good, they are harmless.

Zionist Jews. Most Jews possess an unshaken affinity to the State of Israel. In the same way that Jews feel piety towards the Torah, they also feel attached to their ancestral homeland. To a degree, this is probably true for some of America’s other minority groups: The Armenians, the Mexicans, maybe even the Irish. This too is understandable. However, a minority tied to an external polity must be extremely cautious and remain conscious of the meaning of republican virtue.

As previously stated, civic virtue means that I and my neighbors assume that we all work towards the good of one another. If my neighbor assumes that I care about her, but my interests actually lie elsewhere, I betray the bonds of citizenship binding me to her. I am being dishonest.

Therefore, this is a question of degree and temperance. It is completely natural to wish well for the wellbeing of one’s ancestral land, rejoice in its folklore, and even (again, to a degree) promote its wellbeing. However, such feelings or actions must never come at the expense of the republic, or at the expense of one’s neighbors who innocently trust that their care for me is reciprocated by me.

Remember: The primary civic bond must be that of a society of citizens. Jews who cannot first be Zionists for America, should be fair to their neighbors and migrate.

Finally, there is the category of a hostile minority. Unfortunately, as a result of mass immigration from incompatible cultures, America’s racial reckoning, and pervasive Wokery, we have a fairly rich gallery of such minority groups: Dissatisfied blacks, vengeful Muslims, liberal Jews, disturbed white women, all clamoring “Racist!” at traditional America.

Such a state of being is clearly the contrast of civic virtue. Further, unlike the Amish case, this is an example of minorities who do the very opposite of keeping to themselves – they make demands upon the core population to contort, warp, genuflect, and ultimately undo itself.

Such minorities, so unhappy where they live, should ideally be encouraged to depart. “Depart then forever!” as the Host of the West demanded of Sauron.

A Basic Framework

In summary, what I tried to do here is offer a framework by which to accommodate minorities and also set appropriate civic expectations. As long as the framework is kept on the side of positive civic virtue, such communities, with bonds that may extend national boundaries or never extend beyond themselves, may add spice to the life of a nation. Like salt on a stew (borrowing from John Derbyshire).

If the framework is not kept, the result is much hostility and internal warfare. France’s demographic challenges are but one of many such examples.

Then let’s all heed Cicero’s advice: Our country expects our nourishment and we must all provide it.

Follow us on Twitter!

And sign up for updates here!