The Book of Burke

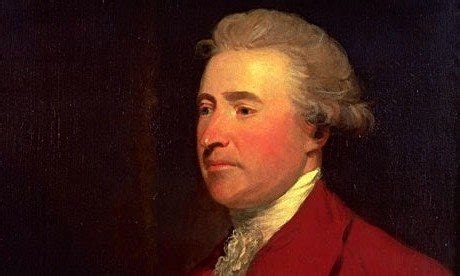

All roads lead back to Edmund Burke. The father of modern conservatism, a British statesman, thinker, and orator, was horrified by the experience of the French Revolution. Even before the great carnage of 1793, as early as 1790, Burke had predicted the revolution would lead to nothing but death, smoky ruins, and destruction.

Obviously, he was right. The French Revolution had oscillated between all the forms of government known to mankind – a constitutional monarchy, a dictatorial republic, a junta-led republic, a dictatorship, and a constitutional monarchy – and that’s just between 1789 and 1815. During that time about 1M-1.5M men and women had perished from starvation and persecution inflicted by the revolution itself (including the mini-genocide of the Vendee), and the Napoleonic wars.

Burke laid out his thoughts about the Revolution in a long-letter type essay known as “Reflections on the Revolution in France.” As amazing as Burke’s predictions were, more amazing is his analysis. Burke saw the revolution as the political manifestation of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, in turn, he saw as an attack by a “literary cabal” against traditional mores, ancient institutions, and the complex yet not-clearly-defined ties that bind society together.

In the harsh ideological triumphalism of the early Revolution, Burke identified the imposition of “geometric logic,” of abstract universal principles imposed as means of utopian re-engineering upon a people planted in history and place. He predicted how the strict categories of “human rights” will result in nothing but the blasting of French society and its plunging into chaos, which could only be arrested by the use of extreme violence.

In that, Burke is the ARCHETYPE of the conservative seeing through revolutionary platitudes and universal principles, naming them for what they are – an attack on the settled lives of ordinary people. Burke taught us to identify and unmask the revolutionary zeal, always cloaked by cries for “social justice” wherever it may appear – nonsense such as the proletariat utopia of the Bolsheviks, the dismantling of the “Four Olds” by Mao’s Red Guards, the “liberation” of the 1960s, and the silly “Open Borders” and anti-“System Racism” movements of our day.

For Burke, society is not an “idea,” a creed, or any manifestation of abstractions. It is an alliance. It is a trust charged by the dead to the living, in keeping for the unborn. Society for Burke is a partnership “not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” in turn human custom and tradition for Burke is not something to be understood through abstraction, but quite the opposite – through prejudice and piety.

“In this enlightened age I am bold enough to confess, that we are generally men of untaught feelings; that instead of casting away all our old prejudices, we cherish them to a very considerable degree, and, to take more shame to ourselves, we cherish them because they are prejudices; and the longer they have lasted, and the more generally they have prevailed, the more we cherish them.”

“Prejudice” for Burke lacked the negative connotation it has today. Like Herder’s idea of kultur, he means the traditions handed down to us and which form our basis of trust and cooperation. Such traditions, being ancient and suffused as they are into our very institutions, cannot necessarily be explained in a “geometric” or abstract sense.

Burke was no fanatic. He observed that to “conserve we must reform.” Meaning, it is upon us to adapt the legacy trusted to us based on the changing circumstances of the time. That way the legacy remains alive useful. It is through such an idea of society that we achieve immortality. Our own brief lives come and go, but our institutions endure, composed of innumerable contributions, mostly anonymous yet meaningful, throughout the generations.

4 Replies to “The Book of Burke”